RIP Gerry Cottle

“Please do not under any circumstances try to find me. I have gone for ever. I have joined the circus. You do not understand me. You are not listening to me. I do not need O-levels where I am going.”

The amazing life of Gerry Cottle who ran away to join the circus when he was 15 and, despite being a josser, ended up with his own circus.

OBITUARY Gerry Cottle

from The Times Thursday January 14 2021

While other rebellious, angst-filled teenagers might have threatened it, Gerry Cottle actually did it: he ran away to join the circus when he was 15. He made a tape for his parents which a schoolfriend played down the line from a phone box: “Please do not under any circumstances try to find me. I have gone for ever. I have joined the circus. You do not understand me. You are not listening to me. I do not need O-levels where I am going.”

The headstrong Surrey schoolboy had decided that he would one day own Britain’s biggest circus after his mother and father had taken him to see Jack Hilton’s circus at Earls Court in 1953 as a Christmas treat. He was transfixed by the polar bears. “A tiny East German lady in a saucy costume had these huge white beasts jumping through hoops and sliding down slides,” he wrote. “It seemed impossibly glamorous and dangerous and exciting. The women were beautiful and sexy, the men rough and macho. They did not look like my parents.”

Cottle spent his life running away from respectability, and the circus provided the ideal escape route. With taxmen and vatmen never far away, he had to be constantly inventive. In 1992, while the country was in the middle of a debate about foreign labour, he cashed in, causing a furore when he hired an American clown, a diminutive black woman named Danise Payne. His publicist, the equally inventive Mark Borkowski, provoked other clowns into going on strike, got his client on to the Today programme and organised a protest at Heathrow for Payne’s arrival. Heathrow’s press officer told Cottle that he had got more press action than Madonna’s arrival the previous week.

When circus animals became a political cause celebre, he got rid of his, briefly becoming the darling of left-wing liberals. There remained, however, a duck which quacked in time to a clown playing the trumpet. “But would you believe the London borough of Haringey had a special meeting to ban that bloody duck?” he wrote. “Benny Hill said he couldn’t believe it.”

By the mid-Seventies, Cottle had his wish: the biggest circus in Britain. His Big Top could accommodate 1,500 and he required 150 trucks to go on tour. “I guess those glorious years in the mid-Seventies were my heyday,” he said. “I felt pretty invincible.”

But the romance and adventure of the big top did not provide all the elements of the unconventional life that Cottle craved. He hardly drank, but in 1983 he was introduced to cocaine by a “blonde, amazonian” prostitute named Kerry whom he picked up near Marble Arch. “Cocaine and I fell in love instantly,” he said. He and Kerry developed a relationship based on mutual consumption: Cottle recalled once slipping away from a family party to see her. The session turned into a three-week binge.

There were more binges and more prostitutes. He went into rehab, where he was told that he was primarily a sex addict, and that cocaine was simply part of that addiction. He gave up drugs for a while, but relapsed when day-to-day life was too boring. He suffered kidney failure and was on dialysis for a month. Finally, in 1991, when “I got in with some bad boys”, the police received a tip-off and stopped him on the M25 with 14 grams of cocaine stashed under his seat. He was fined £500 at Chertsey magistrates’ court. This time he stopped for good.

Gerry Ward Cottle, born in the unbohemian Carshalton, Surrey, in 1945, had strayed far from his deeply conventional roots. His father, Reg, was a stockbroker and grand master in the Freemasons; his mother, Joan, had been a BOAC air stewardess. She wanted this “rather intense posh Surrey schoolboy”, as he described himself, to be a civil engineer. He attended Rutlish Grammar School in Merton Park, alma mater of another boy with circus associations, John Major, who was two years older. “I hated school and I think John Major did too,” he wrote. “Instead of geometric tables and Latin primers, I had dedicated myself to learning the arts of juggling, clowning and walking the tightrope. My Latin master said I was the most hopeless pupil he had ever come across.”

After his trip to Earls Court he had begun practising his skills in the garden, juggling oranges and lemonade bottles, walking on stilts round the outside of the house clinging to the guttering. When Reg was organising ladies nights at the Masons, he hired Gerry to entertain, and he became a minor local celebrity, opening fêtes as a juggling clown.

Five miles away, Chessington Zoo had a permanent circus, and he got in there, mucking out the horses, tidying the seats and clearing litter. He graduated to selling candy floss and was given proper juggling lessons.

His headmaster came to his aid when he ran away to Roberts Circus. His father persuaded him to return and said that he would give his blessing to Gerry’s departure if the head concurred. Cottle Sr was presumably expecting him to demur, but instead the head backed Gerry, who was on the next train back to the circus. “In the short term I was running away from my O-levels, but in the long term I was running away from the dull, boring world that was British suburbia in the 1950s.”

Though he worked on his skills with Roberts Circus, he was largely restricted to menial tasks. “Shovelling up elephant shit is definitely the worst job in the circus,” he said. But he kept a notebook, recording how well they did in each town they visited, accumulating practical knowledge.

Advised to find a smaller family circus, where he would be able to try his hand at anything, he spent three years with Gandeys Circus, alongside such acts as Ivan Karl, the world’s smallest strongman, and Billy Gunga, the Indian chair balancer. He did more juggling and clowning, but Old Joe Gandey also taught him the basics of managing a circus.

He had first met Betty Fossett, scion of one of Britain’s oldest circus families, when he was 17 and she was 12 and he was having a “brief but intense fling” with her cousin Pauline, a juggling rope spinner. Not only was Betty easy on the eye, but as a “josser” — an outsider — if Cottle wanted his own circus he would need connections.

Partly because he needed experience, partly to see Betty again, he joined the Fossetts’ James Brothers Circus, doing some juggling, but more importantly doing the books and the publicity. By then she was 15 and a skilful trick-horse rider. They were married in 1968. With Brian Austen, a fellow circus performer, he formed the Embassy Circus, backed by a circus-loving Tesco director who had inherited a circus through bad debt. They set up on a pig farm outside Reigate, and within four years had two circuses and 60 staff.

By then the Bertram Mills circus had closed, the Chipperfield’s had gone to Africa, and the Smarts had gone into safari parks. Cottle now had Britain’s biggest circus and he was bursting with ideas, such as getting his Iranian strongman to lift an elephant. “Nearly killed the poor old bugger, but he liked it,” he said in 1976. “We run a car over him now.” There were many television appearances after he made the cover of Radio Times when he featured in a documentary entitled What Do You Expect, Elephants? He received a cheque from the BBC for 19p, which he framed. But the circus became crippled by debts, and when he lost £70,000 from a tour of Iran on the eve of the revolution, he was bankrupt.

He managed to set himself up again, but the growing clamour over the use of animals nearly floored him for a second time. In 1984 he pioneered animal-free circuses (apart from the Haringey duck). “If only the whole country could have been Islington, we would have been fine,” he said.

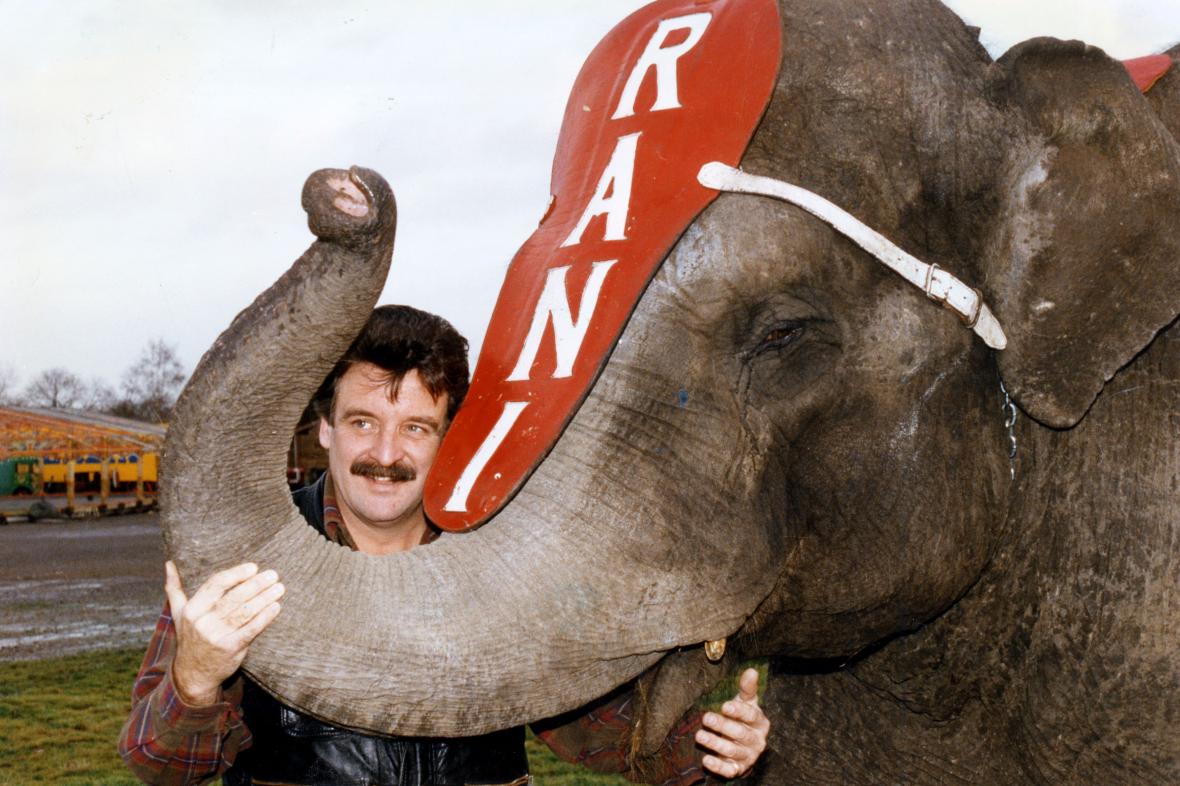

Irrepressible, he soldiered on. Borkowski got him on to Desert Island Discs, Jim’ll Fix It and Wogan, and there were well-publicised stunts, such as a wire walk between Wembley’s towers. His elephant, Rani, became a star in her own right: she opened the Christmas season at Harrods, featured in the Royal Variety Performance, and carried Ken Livingstone, then head of the GLC, to the opening ceremony of the Peace Pagoda in Battersea Park.

In 1989 he opened at Wembley Conference Centre, with Jeremy Beadle as ringmaster, to huge acclaim. There were many disasters, such as a travelling aquarium he took round Ireland, but his resourcefulness rarely faltered. In 1993 when a troupe of Tanzanian acrobats were refused work permits he ordered them to run up and down each other outside the relevant bureaucrat’s office. The permits were granted.

In 1995 he stormed back with the Circus of Horrors. “We have arms and legs flying all over the place,” he told the press. “We’ve even got this chap with a wooden leg which we saw off and hand back to him while everybody sings Always Look On the Bright Side of Life.”

There were some problems, such as having his human cannonball quit on him because he had become too fat for the cannon, but he had the brilliant idea of holding auditions in every town they visited, generating huge publicity. Gary Stretch, the man with the elastic skin, was one of his discoveries.

He went bankrupt again, however, and his private life was also unravelling. Betty finally tired of his relentless womanising, and after several years of living essentially separate lives they parted, though remained married. Cottle’s next affair was with Anna Carter, of Carters Steam Fair, and she moved with him when he bought the Cheddar Gorge tourist attraction Wookey Hole Caves, to which he added a theatre, a circus school and museum and a hotel.

The three daughters he had with Betty, Sarah, April and Juliette-Anne, known as Polly, all joined him to work there. As soon as they were able, they had formed the Cottle Sisters Circus, but the brutal economics their father had suffered from affected them too, and it closed.

In a recent interview with The Daily Telegraph Cottle reflected that Wookey Hole had been his best purchase. His worst, he said, had been the world’s longest limo, 72ft with a hot tub in the back. “It wasn’t much fun trying to get it around the South Circular.”

Gerry Cottle, circus owner, was born on April 4, 1945. He died of Covid-19 on January 13, 2021 aged 75.